Conversation between ANNE-CLAIRE SCHMITZ, JOANNA ZIELIŃSKA and CÉLINE GILLAIN

SUPERHOST CURATORS: You are mainly known as a musician and performer, but your practice consists of an expanded terrain that also involves education, activism, and other diverse forms of creation. Can you say something about your trajectory as an artist and how it has informed and defined your posture?

CÉLINE GILLAIN: My artistic trajectory started with painting, which I did for ten years. Then I had a sort of epiphany when I started working with a collective. Possibilities were multiplied and the range of methods, tools, and strategies were widened. We were loud, fun, and could operate as a kind of guerrilla group. We did what we wanted without asking for permission. DJing also played an important role; it allowed me to not only become visible and occupy a sonic space, making people dance also felt very empowering. DJing helped me break a cycle of silence and invisibility, both in my personal life and as a woman in society.

The field of contemporary art is a unique and privileged place to work in because as an artist you’re free to do what you want—which of course also implies a big responsibility. However, it’s also a very codified milieu, with hierarchies that you can’t really understand unless you’re a part of it. In the music industry, in experimental music, or in academics (where I’m also active), there are other codes, other rules, and also different people who rarely mix or even meet. Categorising mediums, genres, and contexts separates people; it not only creates limitations but also heightens discriminations and a sense of isolation.

Today, it’s hard as an artist not to become a parody of yourself, navigating the in-betweens has become a strategy: being where you’re not expected to be is a way to escape being captured. One of the reasons why I work within different fields at the same time is to be able to build my own ecosystem around desire and meaning.

I feel there’s a constant connection or movement between intimate and collective experiences in your work. What does that interrelation say about your methodology and interests? Does it feel necessary to keep the intimate and the public in proximity?

While working as a teacher in the early 2000’s, I was often confronted with situations where I was not treated equally to my male colleagues. Despite the fact that feminism wasn’t such a hot topic at the time, I sensed that I wasn’t the only one having this kind of experience, and that there was a more structural problem at the root of the issue. Feminism eventually helped me understand that my personal issues are also political matters, and liberated me from the terrible guilt I inherited from the women in my family. Politics have had a direct impact on women’s bodies. My work explores and processes, through experience, how society has conditioned who we are today and how art can help us understand and heal from centuries of oppression.

When I work on a new project, I always start from a personal intuition, a memory of the body, or a desire which leads me back to a larger pattern. I try to link these intuitions and feelings to contemporary politics. I did a whole performance about stage fright that explored the extreme discomfort I felt when performing on stage. It was questioning how being seen and heard sometimes leads to self-punishment and a fear of retaliation, and how that fear is rooted in issues related to class, sex, and race.

Could you expand a little on the idea of vulnerability as a performer?

When I started playing live music, I used to begin the concert by saying how scared and unconfident I was feeling. It was a way to connect with the audience and to demystify the situation by breaking the invisible wall between the stage and the room. But after a while I stopped because the repetition of this gesture although genuine at first started to feel like fabricated vulnerability.

In pop music, vulnerability is a commodity like any other, especially in young white women. Whether it comes from a place of sincerity or not, vulnerability is still used to sell more records. For example, look at last year’s Chanel campaign which saw singer Angèle crying in the photo. You could tell the tears were added in post-production, they were a narrative element of the campaign. Young white women’s fragility sells. Black women on the other hand are supposed to be strong and warriorlike, they’re supposed to dominate or take care of everyone. Both are alienating female archetypes that are still very present in mainstream culture.

On the other hand, showing overconfidence is something we have to do today in order to exist, especially on social media, and as artists. We are the products of our staged lives, performing the stories of our existence. I exist as a “good product” when I’m assertive and in control of my image, when the content I produce is easy to react to. Changing one’s mind, self-critique, and emotional confusion are a lot harder to commodify.

A society that is afraid of self-doubt is one that is consumed by insecurity and existential doubt. Instead of dreading it, I think we should cultivate self-doubt, the not-knowing, and what better place to do that than public institutions or market-free spaces like schools and museums?

Can you share what you have learned about listening within your different working contexts, both from your perspective and that of the audience?

It’s difficult to say because of the parameters inherent to each situation: when the performance takes place (the time of day or night), where it takes place (the type of venue), who hosts the event, how the venue is configured, etc.

What I find interesting in DJing for instance is that it requires you to be aware of the crowd’s electricity. It’s about feeling the energy of the room and maintaining a certain flow. It’s very difficult to do but when it works it’s magical, transformational. I see DJing as a mission to sense, to listen to the context, to be in the moment. Often there can be a discrepancy between how you prepared and what actually happens, so I suppose DJing leads you to deal with anticipation and the unforeseen.

In an experimental music context on the other hand, it’s all about listening, about paying attention. The attention is more acute but it sometimes feels like the body is absent or dormant. It’s a more static way of listening, based on concentration and intellect. I don’t really perform in that kind of context because my music is rhythmic and involves the body.

In a contemporary art context, the audience is particularly open-minded, but it’s also a difficult crowd to impress. I get the impression you’re not supposed to be too explicit, sentimental, or “pop”. That said, it’s still the best place to perform because there are no predetermined expectations and as a performer you can experiment like in no other place.

Lastly, if you’re lucky enough to have some recognition for your work, and are invited to perform in a more mainstream music festival or venue, you’ll be well treated as an artist. You can tell you’re part of an industry and there’s no taboo about money, which can be the case in more intellectual spheres. But you have to deliver a product. People pay to see you. There’s a responsibility towards the audience to perform something recognisable. The time of the performance is also important. Usually, the vibe switches at around 11 pm, people’s attention shifts, often influenced by substances like alcohol and drugs. Then it becomes more about fun and less about content.

These are just a few examples of how listening is conditioned by context. I want to hybridise listening contexts and ask: what happens if you sing during a lecture or talk during a concert? If you do a DJ set that is also a lecture and a listening session? What happens when the museum meets the club?

Your project for Superhost is called ANTENA, would you like to tell us about your thoughts behind this title?

In radio, an antenna is a device used to transmit or receive a wave, a signal. In biology, an antenna (also referred to as a feeler) is an articulated organ of sensation attached to the heads of insects and crustacea.

Our bodies are living and sensuous machines, with millions of captors, sophisticated systems that transform our relation to the world and to the Other into signals and information. The ear, for instance, is an incredible device: it transforms airwaves into vibrations which are then transformed into electrical impulses. The signal goes from outside to inside, from aerial to liquid to electrical. Our bodies are antennae, made of highly advanced technology. Just like the earth we live in, the sensory machine that is the body is intelligent because it feels. And somehow, we’ve more or less lost touch with that, as individuals and as societies. Audre Lorde, in Uses of the Erotic (1978), says it well: “[…] it has become fashionable to separate the spiritual (psychic and emotional) from the political […] In the same way, we have attempted to separate the spiritual and the erotic […]”.

ANTENA asks: What does the body as an antenna have to teach us? It aims to (re)connect the political with the (individual and collective) body, and with the erotic. Lastly, the museum is also an antenna, we can imagine it as a “feeler”, an organ of sensation attached to the head of the city.

What do you expect from ANTENA? How does the cycle relate to your practice, and to the current context of the year 2023?

Because it is articulated around listening, ANTENA is a project that connects all the dots of my practice. In 2023, questioning listening is an opportunity to think about how we manage our attention in an increasingly loud and oversaturated world. Indeed, how can we develop a more environmental attention, based on reciprocity and less on consumption, competition or profit, in order to care for the relations that sustain our individual and collective life? How can we also decolonise listening, and expand critical sound practices? ANTENA explores topics such as: queer and female voices and the idea of disobedience; the transformational and healing potential of rhythm and electronic dance music; sonic patriarchy; interspecies listening; music and pleasure as vectors of change.

Halfway between a safe.r space and an observation post, it seems your project holds a double dynamic, both introverted and extroverted. How does that resonate with you?

I’ve been working as an art professor for 20 years in many different contexts but mostly in public institutions. Schools, like museums, are inhabited by communities that are driven by progressive dynamics, yet, they are built on structures that are reluctant to change. ANTENA is an experiment about listening from within the institution while also listening to the institution. What will we hear if we listen to the womb of the institution? And what will happen if we sing our hearts out inside that womb? It’s as if we’re inside a big body, like Pinocchio in Monstro the whale’s belly making a fire to provoke a sneeze. Because sounds are vibrations, they have the power to make the walls tremble.

Museums belong to the rare spaces within the fabric of Western societies that remain (almost) free. Despite their apparent accessibility they often remain or feel inaccessible to large parts of the public. What are your thoughts on this?

Museums and public institutions (like schools or hospitals) lie outside the logic of profit and inside a logic of care, and so are devalued in our current capitalist societies. They’re taken for granted by many, and as we saw during the pandemic, such structures aren’t actually a given. They need to be constantly fought for in order to exist. We must advocate for the survival of these agents of democracy and their survival depends on how they’ll be able to transform, to open their doors to the street.

It’s our responsibility to open practices up, to dismantle the binaries of high art/low art, intellect/body, serious/fun, political/intimate, pop/experimental. I know it’s easier said than done but a public space where we can think together doesn’t have to be elitist, it should be inclusive.

What role can the museum play today?

A museum has a particular status that is simultaneously fully part of the life of a city and distant from it. This somehow “outsider” position can contribute to creating renewed desires, imaginaries, and zones of human resistance. The museum is a rare place where we can collectively think, meet, and celebrate being alive outside of our families, religions, or work.

The museum exists at the crossroads of past, present and future. The future is intimately linked to the past, because it does not exist without the idea of continuity. In that sense, the museum has ghosts in (and on?) its walls, it questions our conceptions of how the past shapes the present, while at the same time suggesting a certain potential way of inhabiting the future.

An important part of ANTENA is the formation of a choir. Can you share how that idea of a format involving collective labour came to be?

Working collectively and exploring group dynamics are ways to think about democracy. Both the joy and the tension and chaos of working together can be used as material to create new narratives, and to explore the notion of futurability.

I had the project to create a support group for a while, like an AA group but for patriarchal capitalism survivors. A place where you get to meet people from any background who are struggling in patriarchal capitalist society (everyone?) and talk, drink coffee, eat cake, and share a common experience. Parallel to that I’ve been wanting to start a band to experience collectively around rhythm, voice, and time-based improvisation. So, it felt coherent to mix both ideas for Superhost and create a choir that while acting as both a support group and a band, would also be neither of them.

The choir is an experiment around the idea of building a collective song. Using our voices in all sorts of ways, exploring what it means to be loud or not, and what it means to occupy sonic space as a group.

The psychic, almost magical power of words sung, spoken, or yelled might open some gates. We’ll create bizarre beats inspired by techno and dance music with makeshift homemade percussions. Rhythm can lead to a trance and has the potential to shake the walls, create a crack in the system. As contradictory as it may seem, rhythm creates change, rhythm leads to transformation.

What links are to be made during ANTENA between rhythm, female desire, and listening?

The origin of the word “listen” is the middle English liste, which means desire. ANTENA explores the way occupying sonic space is related to exploring oneself, one’s voice, to defining one’s desire. Female desire is not only women’s desire, it’s the name of a rhizomatic desire that needs to be decolonised, a desire that is not about control or domination.

What do women want? Every woman wants different things in her life, but for such a long time a woman’s desires were designed to serve power structures and maintain social order, not question it. Women’s desire has been linked through history to their ability to be desired. Their survival has depended on their ability to make themselves desirable. But how can we ever know what it is that we want, rather than what we have been taught to want? Why do women still find it so hard to express and to understand their deepest desires?

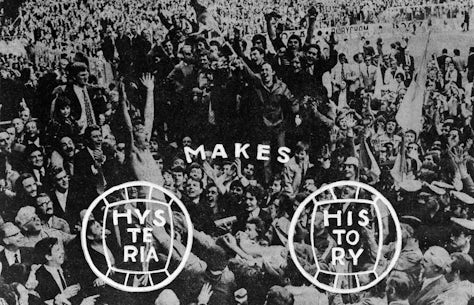

Music has everything to do with desire and rhythm has everything to do with body intelligence, with the body’s intuitive healing forces. Western culture has associated rhythm with popular culture, the industry, the queer body, the female body, the Black body, creating a sort of cordon sanitaire around it. Rhythmic music has been decreed an unserious matter, having no intellectual value whatsoever. Take club music for instance: it comes from disco, from marginalised, mostly queer, Black and Latino communities in the US, it’s originally music for bodies moving together, bodies who have nowhere else to go to meet each other. It is social, sexual, pleasurable, and powerful. But the mainstreaming of club music has stripped it of its subversive substance, in the process of making it a very lucrative business.

But it is also changing now. Despite the fact that artists are paid less and less and are hardly considered at all due in part to streaming platforms like Spotify, access to technology and knowledge has led to an incredible democratisation of music production. Indeed, access is allowing the emergence of multiple genres and a hybridisation of electronic rhythmic musics, restoring little by little and re-inventing their political, critical, and conceptual value.

ANTENA’s approach is one that deconstructs preconceived ideas and conventions about music, and explores how listening, rhythm, and female desire are historically connected, and how those connections can open up new worlds.